esbuild and Redis1 are two examples of codebases with exceptional documentation.

Through their READMEs, changelogs, architecture documents, and code comments, both projects explain their design in such a way that someone new to the codebase can understand where things are, how things are done, and why they are done that way.

If you’re a developer looking to get better at documenting your code and software architecture, these are great case studies.

Why good documentation matters

If you’re writing software, good documentation is a necessity, especially if other people will see or contribute to the codebase—or if you yourself plan on coming back later.

If you’re only using the software, you almost always could benefit from documentation that is missing, whether it be instructions on how to use it—or an explanation of when you should and shouldn’t use it.

If you’re contributing to a codebase, the speed at which you can start effectively contributing is correlated to how good the documentation is, as long as the code itself isn’t convoluted.

Whether you’re an author, contributor, or just an end user of the codebase, the quality of the documentation affects your experience, directly or indirectly—so writing good documentation matters.

The benefits of good documentation are too many to list. Here are a few that might apply to you.

- You save time, especially if you’re working with a team. Instead of explaining the entire codebase for an hour to each person who joins your project, though that is beneficial itself in a number of ways, they rather read the documentation ahead of time, resulting in a more productive discussion when you do talk, as it’s not a one-sided conversation.

- Your open source project is more likely to receive outside contributions and therefore keep existing after you can no longer maintain it.

- Past decisions that you’re now questioning have been recorded, preventing you from accidentally reintroducing a problem that a past decision helped to resolve.

- More people can use your application or library, because fewer people have to figure things out for themselves.

- It helps structure your thinking—and reveal flaws. When writing, you have to explicitly consider and record what you’re thinking, and it brings to light potential problems that you otherwise wouldn’t have noticed.

With this in mind, let’s look at and learn from two open source projects that have excellent documentation.

esbuild

esbuild is a JavaScript bundler created by Evan Wallace. It’s not important for this analysis to know what a bundler is, but webpack has a good explanation if you’re curious.

esbuild’s README

A project’s README serves as the entry point for a reader of the code. It’s where they get oriented, so it’s important to not overwhelm them with information. Likewise, it’s important to point them to different areas where they can learn more.

This README focuses exclusively on the end user of the tool.

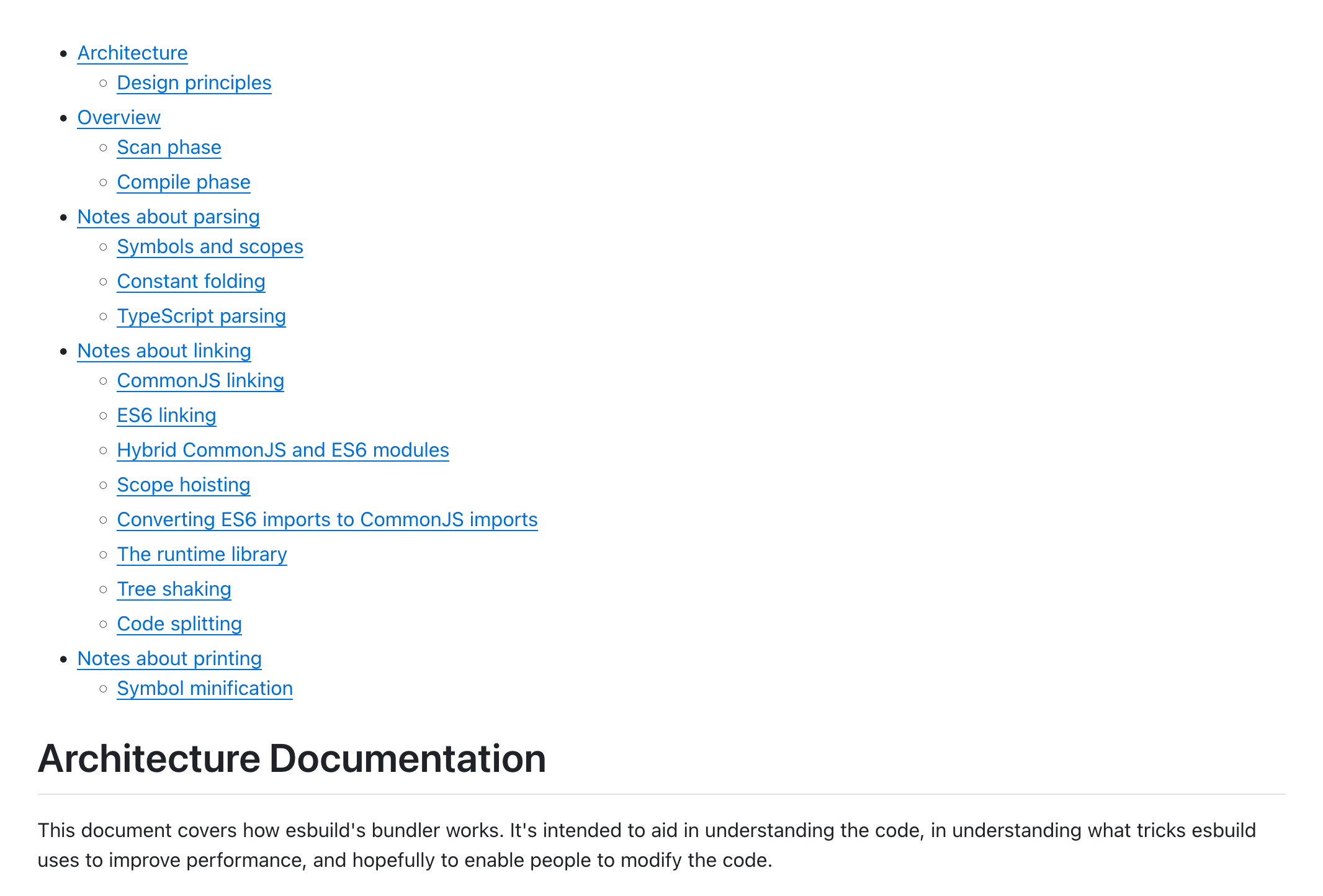

It first links to major sections in the documentation, such as the getting started section, allowing someone to jump to the topic they’re looking for.

The only other section is titled “Why?” and explains briefly why someone would choose this JavaScript bundler over others, with a visualization to help understand the reason. This section also lists the features of the tool, providing an overview of what it does, which helps someone determine if it meets their needs.

And that’s it. Starting from here, someone can explore the FAQ, the getting started pages if they wish to use it, the API documentation, or the documentation for a specific feature. It’s hard to get lost.

esbuild’s architecture documentation

Although the README doesn’t mention the code architecture—its audience is the end user—esbuild is certainly not lacking in architecture documentation.

Inside a directory called docs are two files: architecture.md and development.md. It’s easy to find what you’re looking for. We’ll focus on the first file.

The document starts with a table of contents to help find things and an introduction which explains the intention of the document.

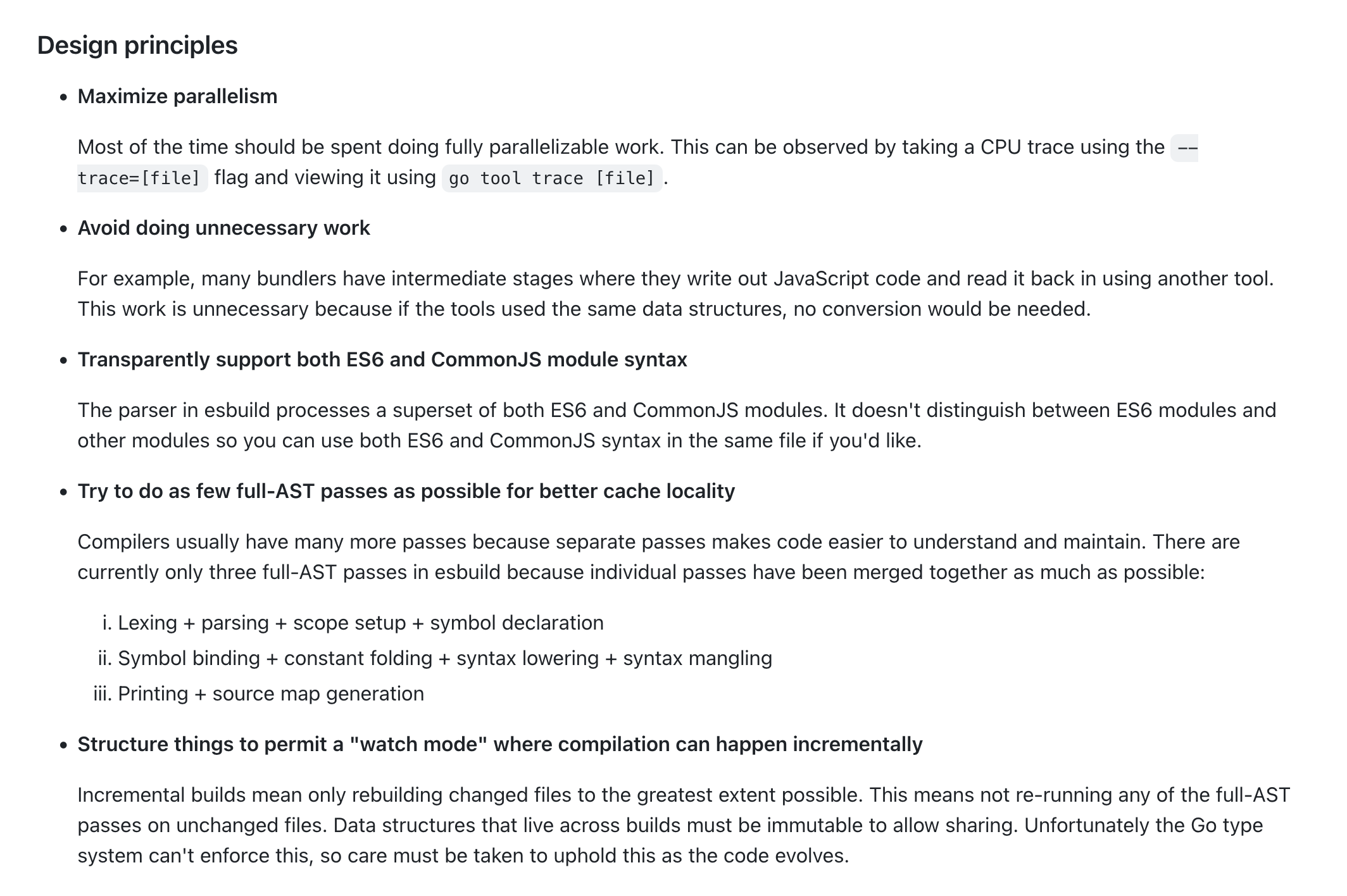

After the short introduction, it talks about the design principles. This is important because it sets the foundation for the decisions that follow. For anything not explicitly explained in the later parts, we wouldn’t be wrong to assume they are a result of these principles, and can infer the reason for an unexplained design choice.

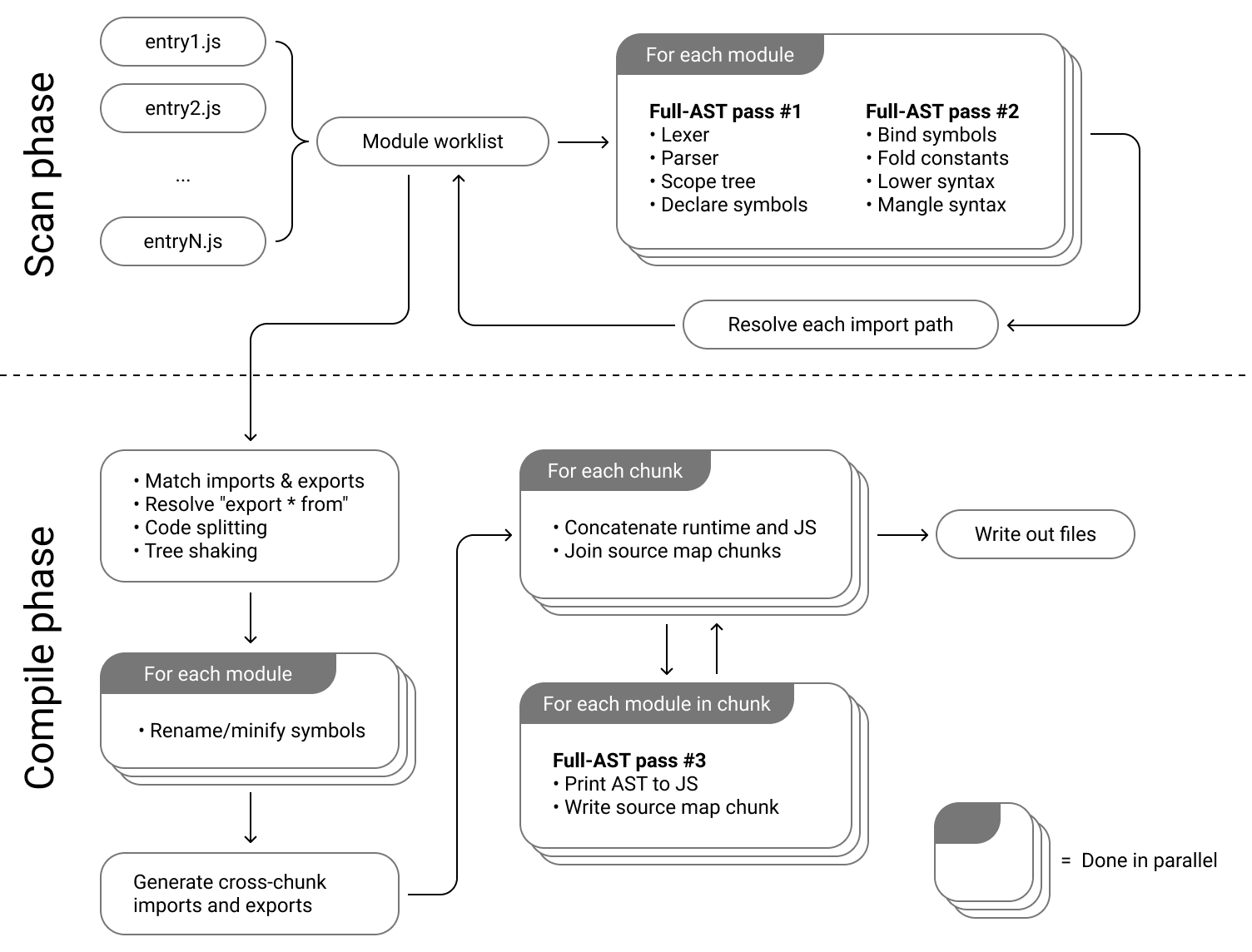

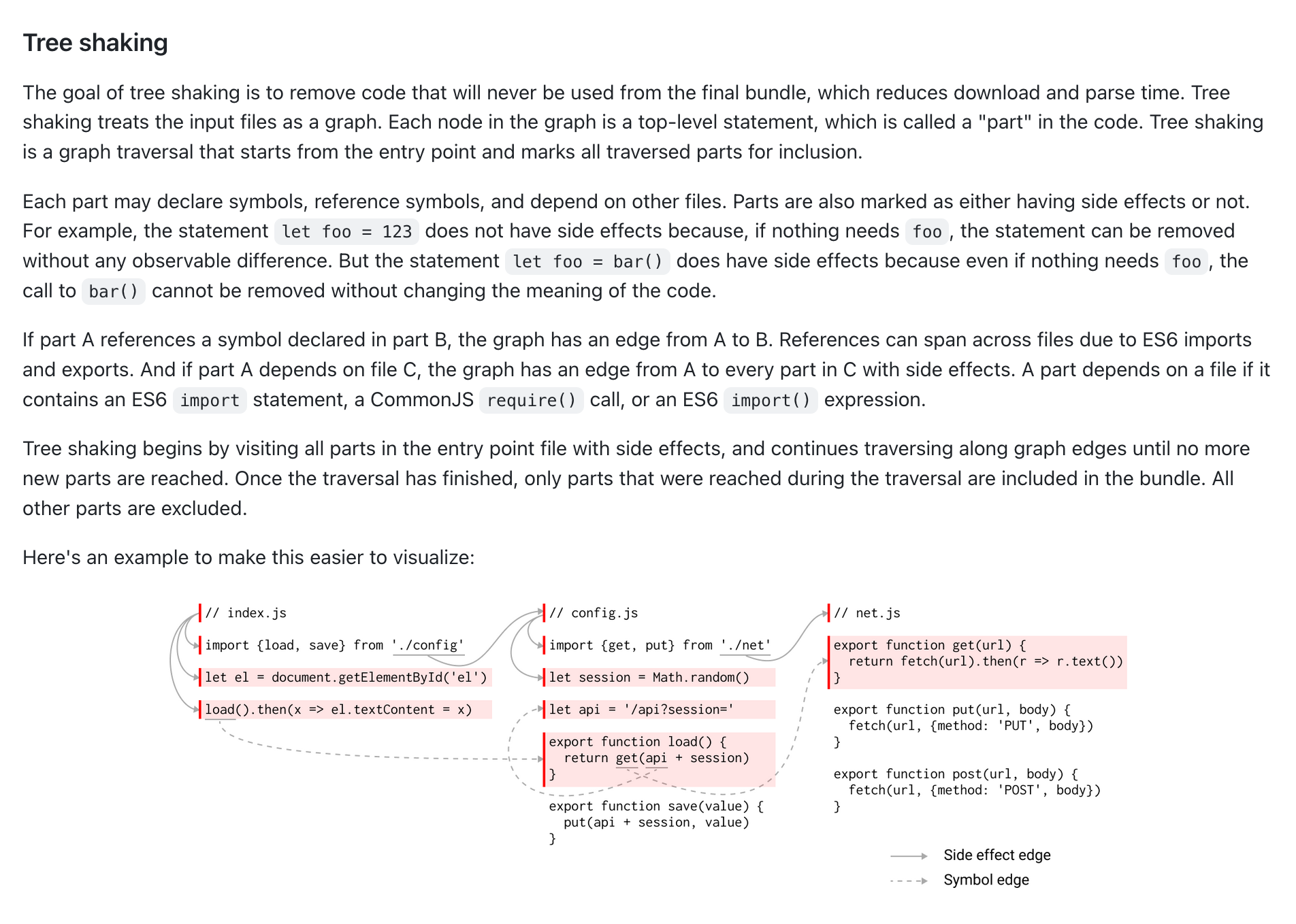

Another thing done well is that it’s not all text. There are plenty of graphics to help explain concepts. Below, we see a graphic which shows the different phases of how esbuild bundles JavaScript, including an indication of which steps are done in parallel.

Graphs with nodes and edges are useful if the process you’re explaining involves steps that loop back to each other, which can be hard to get across by textual description alone.

The visuals mix in code as well, such as in the below example which shows the traversal of the program through code during the tree shaking process.

The rest of the architecture documentation for esbuild is similar. It explains a lot in text, but also provides graphics to help visualize complex concepts. Code snippets, tables, and formatting are abundant to aid in reading and understanding how and why things work the way they do.

esbuild’s changelog

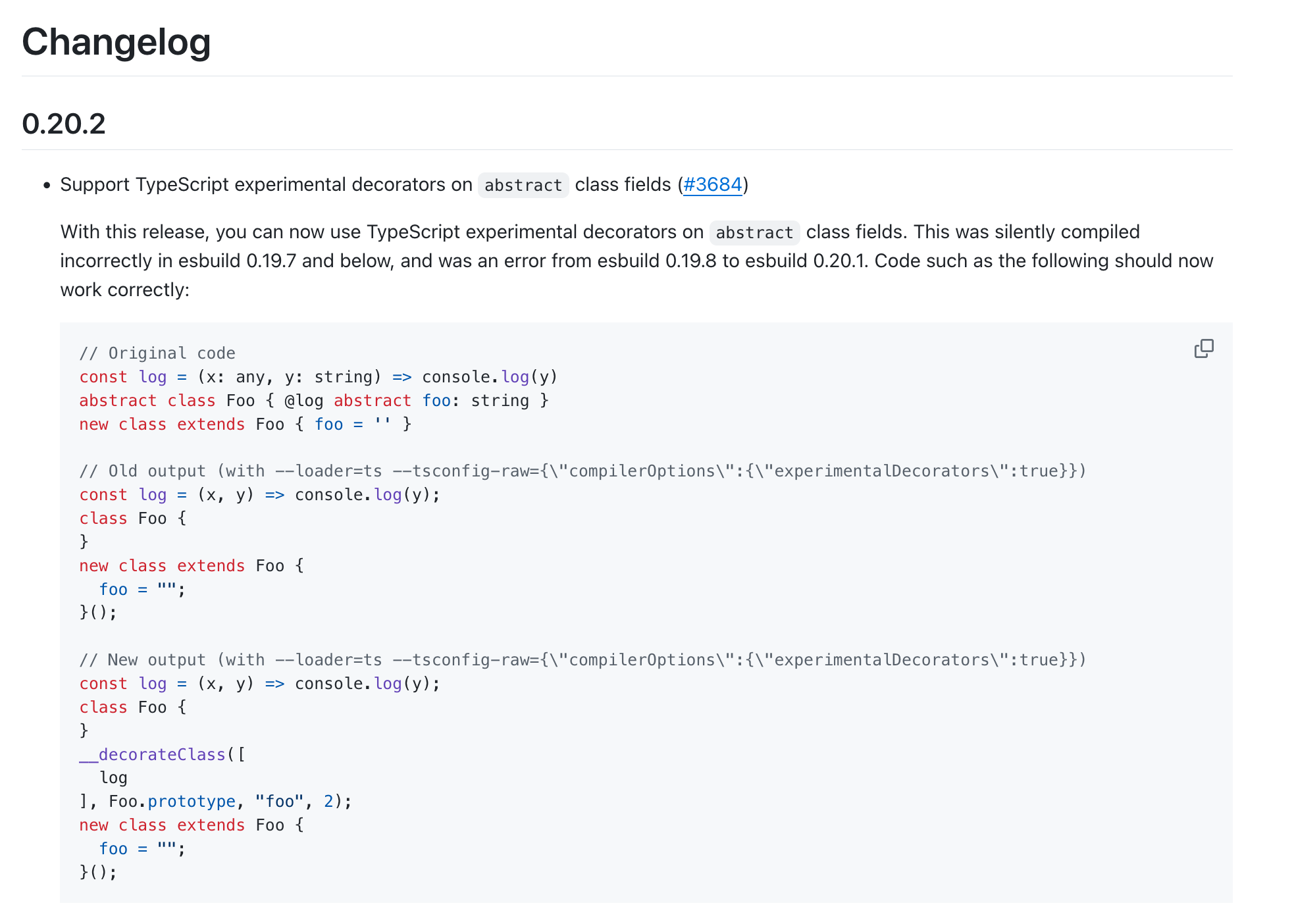

esbuild’s thorough documentation doesn’t stop at the architecture—it extends to the changelog as well.

This entry in the changelog has a summary, an extended description, and example code showing the output before and after the change.

What’s impressive is that every entry is like this. Detailed explanation2, example code. Someone reading through the changes can understand the impact without referencing the actual code modifications.

The result of esbuild’s good documentation

It’s not enough that esbuild is a fast JavaScript bundler to win people over. The detailed documentation has no doubt played a role in its growth. At the time of writing, it has 37,000 stars on GitHub and is used by 4.6 million projects.

Although Evan is the main contributor by far, there is still no doubt that the documentation has helped get the project to where it is today by serving as a form of thinking—it may be the only way to wrangle such a complex system into one’s head.

Redis

Redis is an in-memory database. As with esbuild, any more explanation of what Redis does is out of scope for this post, but what is in scope for Redis is the level of detail in the documentation, specifically around its code and architecture.

The Redis README: Introduction and architecture

The README shares many of the good characteristics of the esbuild README, with a couple differences.

First, it’s not short, but that’s okay because the section that introduces Redis is short. The rest of the README is for people contributing to or reading the Redis codebase. This README has a focus on both end users and contributors. For esbuild and Redis, what’s important is that the documentation for both end users and contributors is available—it’s just in different locations.

In the section for contributors, the Redis README talks about compiling the Redis source code, fixing common build problems, gotchas with particular operating systems, and running and installing Redis. It covers the basics and highlights common problems, allowing someone to get started and assisting them in not getting stuck soon after.

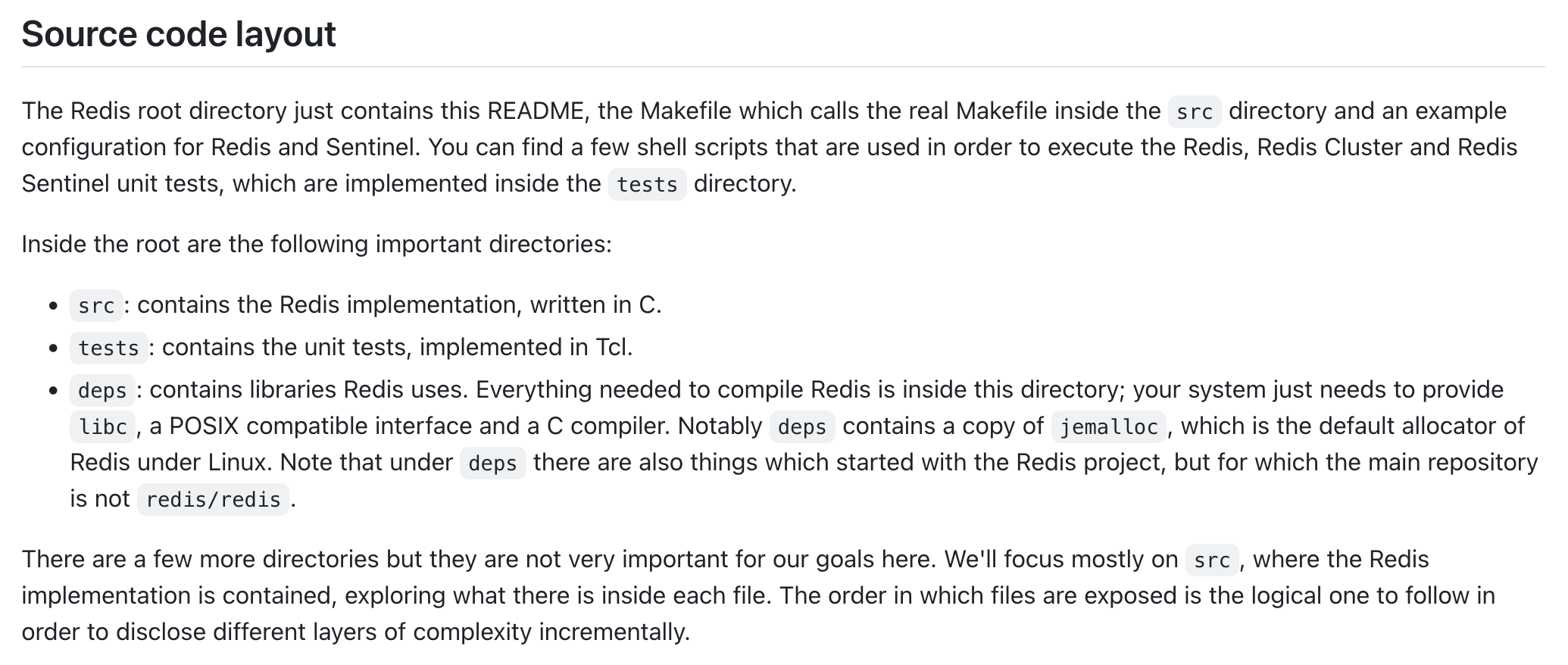

However, the section which really shines is about the Redis internals.

This section begins with the layout of the source code, allowing someone new to understand where to find what they’re looking for, and what directories they might be working in most.

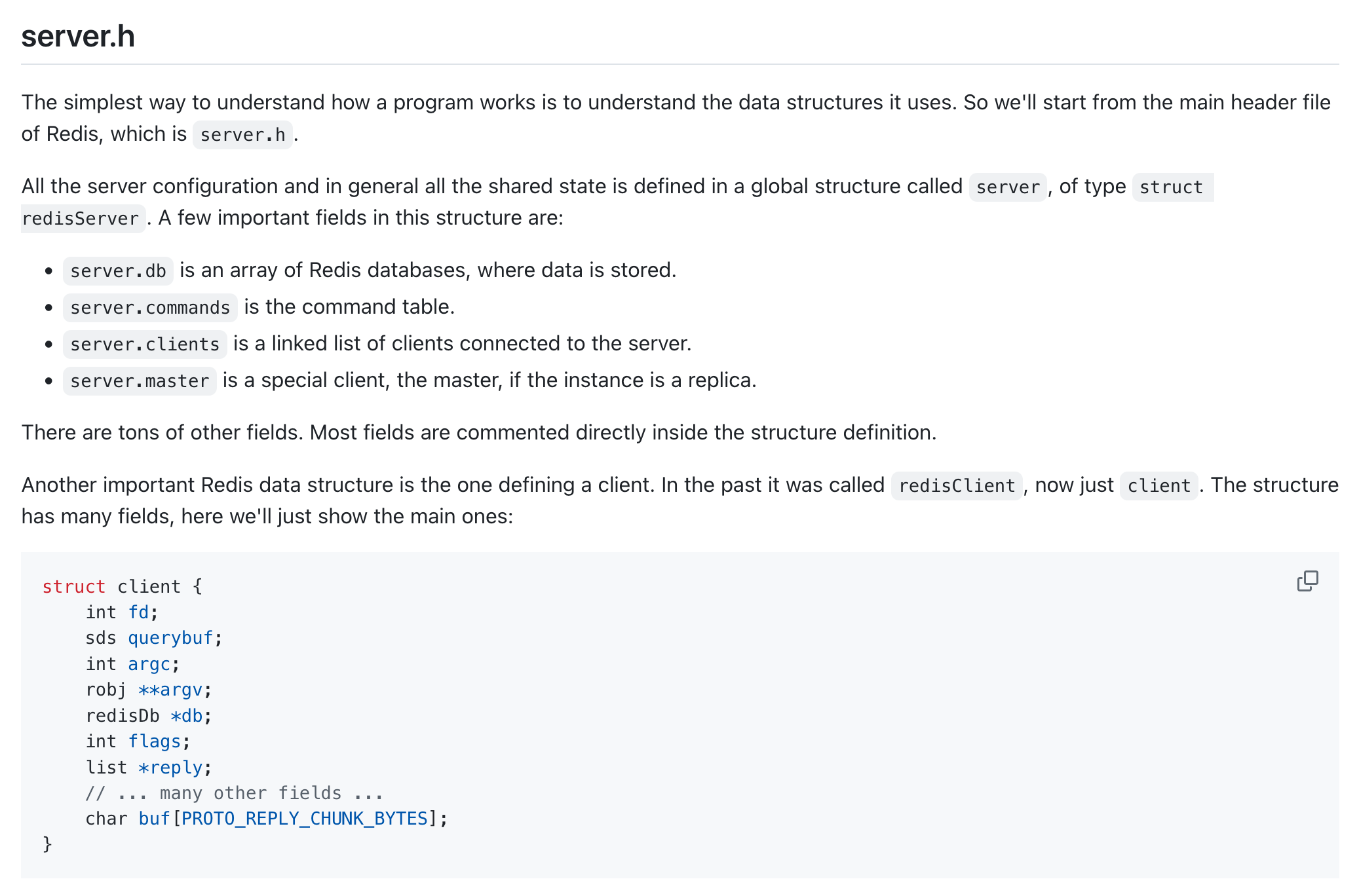

Then, it talks about key files and their structure. This helps someone understand where the control flow starts.

Further down it continues to go over key files, building up an architecture of the program.

Unlike esbuild, the description of the architecture is more compact, yet it’s still wonderful to have, as the other option is to read through hundreds of source code files, some with thousands of lines.

Code comments in the Redis source

Any well-documented codebase usually has good inline documentation in the form of code comments.

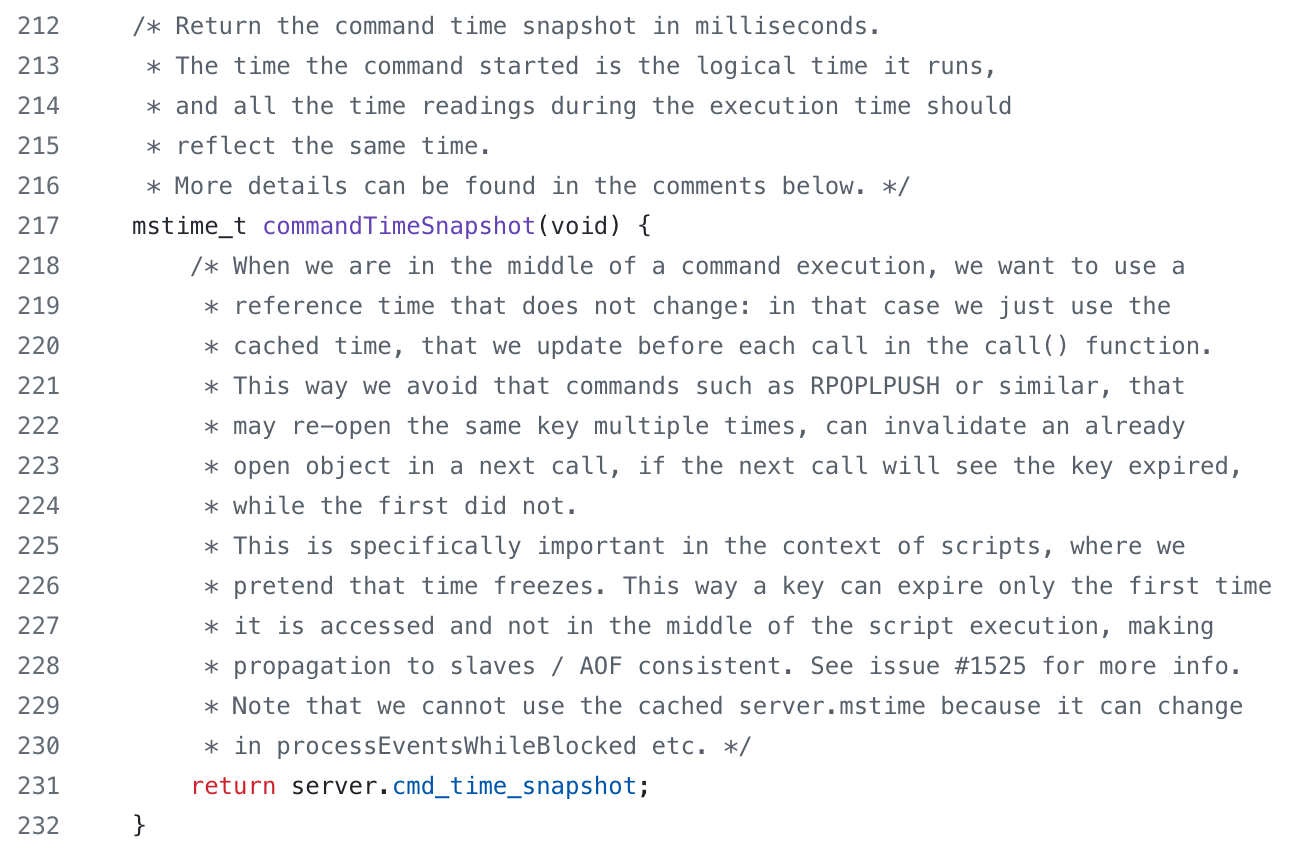

In the Redis codebase, we see examples like the one below, where multiple paragraphs explain a single line of code, providing valuable context.

It’s important to emphasize that long explanations of trivial lines of code are not necessary. If the operation is simple and doesn’t require additional context to understand why it’s done that way, then it’s better to have no comment. A comment which says the same thing as the line of code is unnecessary, unless the line of code is particularly difficult to read (in which case it should probably be refactored), or the intention is to teach.

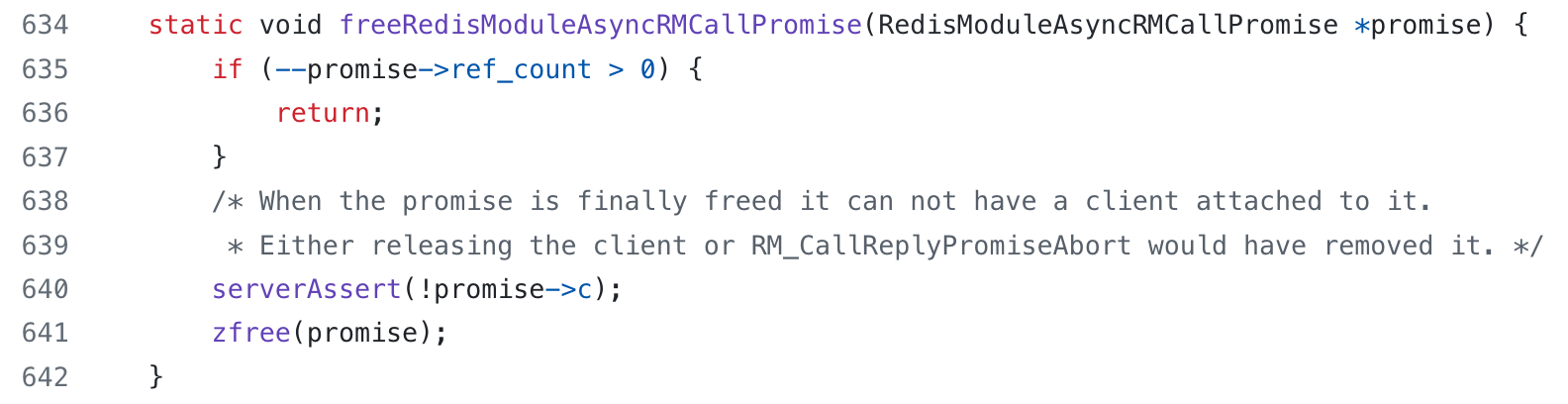

Below we see an example of this, where the line that may be questioned with “why the assertion?” is explained with a comment which assures the reader why it should be correct to assert this.

Wrapping up

There are many open source projects with great documentation. I decided to showcase these two because I vividly remember that when I first came across them, I thought to myself, “wow, this is some good documentation.”

Although time constraints in the moment may not allow for such thorough documentation, what’s hard to see is how much time it saves later on, not just for yourself but for others. Keep that in mind when making the tradeoff.

Some projects are purely for fun, or something that only you are working on and you’re not sure if it’s going to go anywhere. In these situations, it’s okay to not document anything.

But not documenting anything on a project that many people use or contribute to is something you may want to reconsider.

If we’re going by the definition from the Open Source Initiative, with recent license changes to prevent cloud providers from commoditizing Redis, it’s technically not open source anymore, but its code and documentation are still available for anyone to read and contribute to. ↩︎

I understand that programs used in other programs require an increased level of detail in a changelog compared to a consumer product, since critical systems may depend on specific behavior, but in today’s world of “iterate quick”, it’s good to not forget that iterating quick does not mean doing things without thought. Writing changelogs help with that thinking. Recently I’ve seen products that are more on the consumer side releasing detailed changelogs as well. In the linked example, each entry is a long-ish blog post with images, GIFs, and a written explanation of the change. ↩︎